Hiring a forensic accountant requires due diligence. Your forensic accountant will be providing services to you during a stressful situation, during which they will be conducting an investigation and providing findings related to your matter; and possibly providing guidance to favorably structure a settlement that protects your interests, and delivering testimony that clarifies uncertainties, confirms the accuracy of your position, and succeeds in securing the proper settlement of your case. Forensic accountants impartially and objectively apply accounting, financial analysis, and investigative skills to determine facts, conduct financial investigations, and provide credible analyses and reports that may be relied upon in court, arbitration, and mediation, or by other parties to a matter. They may be called upon to deliver expert witness testimony in depositions, arbitration, mediation, and/or trial settings. This article provides guidance on the factors to consider in your selection of a forensic accountant including personal qualities, experience, credentials, costs, staffing, and resources available to assist in your hiring decision.

Identifying Forensic Accountants

Forensic accountants should possess experience in accounting and financial analysis, strong ethics, discretion, sensitivity, sound professional judgment, curiosity, effective listening, and clear communications skills. They must be able to contemplate alternatives and scrutinize fine details, while maintaining a big picture perspective. While computer forensics is a specialty of its own, a forensic accountant should possess strong, relevant computer skills, or a staff that does, and a complete understanding of how the results of their analyses were derived. Because your forensic accountant may be asking difficult questions while delving into the most highly sensitive, personal and financial details of your life, and their job is not to tell you what you want to hear, but to tell you what you need to hear, it is paramount that the professional you hire is someone whom you not only feel confident in, but are comfortable working with, feel listened to and respected by, and that is capable of understanding and looking out for your best interests.

Experience and professional credentials are two important factors to consider in hiring a forensic accountant. What is their forensic accounting experience? Is this professional familiar with the industry and its nuances, or a similar industry to yours? If not, can they readily obtain this understanding from you or other sources? Have they been deposed and/or provided expert witness testimony before? In the event that your matter proceeds to litigation, does this professional possess the qualifications and utilize the accepted methodology and reasoning to have their analyses, report, or testimony accepted by a trier of fact, mediator, or arbitrator, or will their work be rejected? Do you feel confident they possess the ability to clearly and logically articulate your case before a judge and/or jury, should that occur? Do they possess experience in assisting in structuring settlements?

Forensic accounting experience can be obtained from a variety of sources. Examples include internal audit, government examinations/investigations (ex. IRS, FBI, and SEC), as well as experience with a forensic accounting and litigation support department for a consulting or public accounting firm, a fraud department, a law firm, an insurance company, or a financial institution. A review of the forensic accountant’s resume/CV and/or LinkedIn profile will provide this information. How much experience is sufficient? There is no simple answer, and in fact, a less-experienced forensic accountant, possessing no previous similar-case bias, may ask the very questions or delve into the specific information that is the key to solving your financial puzzle!

Request a sample work product that corresponds to an engagement similar to yours, to review and understand what you can expect to receive. You may only be permitted to review this document on site, and may not obtain a copy, in order to protect the forensic accountant’s processes and work product. Do you understand the sample provided or is it confusing? Are the associated analyses and exhibits clear and logical? Be sure that the sample you review contains clearly supported conclusions.

Forensic Accounting in Litigation

In the event your case does not settle and proceeds to litigation, you will need a forensic accountant that is able to represent you. During your meeting, carefully observe your interaction with the candidate to determine if you feel confident they will be able to clearly and logically explain your case before a judge and/or jury, should that should occur. Find out if the candidate has ever been deposed and/or provided expert witness testimony. If so, did this professional possess the qualifications and utilize the accepted methodology and reasoning to have their analyses, report, or testimony accepted by a trier of fact, mediator, or arbitrator? A Daubert challenge is a hearing conducted before a judge where the validity and admissibility of expert testimony is challenged by opposing counsel. A Daubert challenge relates to the admissibility requirements in Federal Rule of Evidence 702, which state “A witness who is qualified as an expert by knowledge, skill, experience, training, or education may testify in the form of an opinion or otherwise if: a) the expert’s scientific, technical, or other specialized knowledge will help the trier of fact to understand the evidence or to determine a fact in issue; b) the testimony is based on sufficient facts or data; c) the testimony is the product of reliable principles and methods; and d) the expert has reliably applied the principles and methods to the facts of the case.” Has the candidate successfully defended a Daubert challenge, if one occurred?

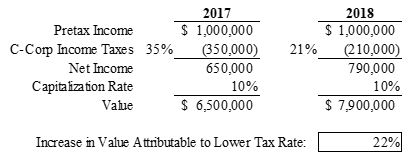

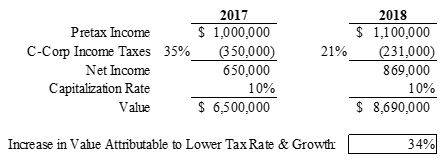

The financial settlement of your case may have short and/or long-term tax repercussions that require thoughtful consideration, as you will be living with the results of this legally agreed to and binding settlement. The financial settlement process occurs at the end of your case, during a time you are emotionally exhausted and may feel ready to throw in the towel, to end your matter and move forward with your life. Other parties involved with your case may be applying pressure to end your case. This is the time you require wise advice to make an informed decision to protect your financial interests and future. A forensic accountant can provide guidance on the different settlement options available and their potential ramifications, sometimes suggesting creative ways to settle a case to the mutual satisfaction of the parties. The candidates you are considering should be able to discuss the ways they can support you at this juncture. Should your forensic accountant lack this experience, you will need to consult with an accountant who is familiar with your financial circumstances and wishes, to protect your interests during this process.

While a credentialed forensic accountant is not a guarantee of quality, it provides some level of assurance and provides legitimacy before a trier of fact, should your case proceed to trial. Some common forensic accountant professional credentials include CPA, CFE, CFF, and MAFF. More details about these credentials will appear in a future article.

Forensic Accounting Costs

After experience and professional credentials have been considered, we consider the all-important factor, cost. The Benjamin Franklin quote “The bitterness of poor quality remains long after the sweetness of low price is forgotten” applies in hiring any professional, and the hiring of a forensic accountant is no exception. While hiring a forensic accountant to represent parties jointly may save money in the short run by avoiding the duplication of forensic accounting fees by the parties, the professional will not advocate for one party over the other during the settlement process. This may or may not be in your best interest. Be sure to think this over carefully, before agreeing to joint representation, if it is applicable.

Forensic accounting deals with unknowns and a multitude of variables, with no guaranteed outcome. Typically, at the outset of a case, the final scope and cost cannot be determined with accuracy, but with an estimate generally requiring revision as the case proceeds. As the initial case work begins, it is common to discover that more work will be required than what was originally assumed, for those very reasons that only come to light as the forensic accounting work is performed. Therefore, it is important to understand what specific costs are involved in your case and what you can expect to receive for those costs. An understanding of what you might do, or not do, to keep costs down is equally important. It is critical that you provide organized information, in the format and within the requested confines, as is required by your forensic accountant, with the understanding that you are contributing to rising fees if you do not. Be prepared to communicate your anticipated budget with the prospective forensic accountant and once hired, to discuss case milestones and unanticipated hurdles openly to avoid any unpleasant surprises. This underscores the importance in hiring someone you feel comfortable working with, as you may be having difficult, uncomfortable conversations with the forensic accountant regarding fees that will be incurred to properly represent your interests.

Staffing/fees, resources and technology available will contribute to your end costs. What components of the engagement will the person you hire be performing, and what parts, if any, will be delegated to staff at different levels and billing rates? If you desire that only the person you hire works on your engagement, consider that you may be paying more for this. What qualifications do “other staff” that may be working on your engagement possess? Will staff be adequately supervised, and their work properly reviewed, to ensure that you receive an error free analysis and report? What resources and technology does the forensic accountant have access to, and how will they be utilized? Discuss the industry and other resources that might be used in your case. Is their technology up to date and compatible with yours? If their technology is not up to date or compatible with yours, additional fees may be incurred to resolve these issues. Details on the different fees relating to your engagement, and for the staff/service levels provided should be discussed and provided in writing.

This article was intended to provide guidance in the selection of a forensic accountant by discussing the personal qualities, experience, credentials, costs, staffing, and other available resources to consider during the decision making process. If you have any questions or comments relating to this topic, please contact me at eonischuk@adventvalue.com.