We recently have been involved in a number of valuation assignments which involved the allocation of personal and enterprise goodwill.

In valuing a business, the term “goodwill” may have different meanings. In many cases, goodwill is used as a catch-all for all intangible assets of a business. However, from a valuation perspective, goodwill is, “the excess value of an enterprise beyond the value attributable to the entity’s identifiable net assets.”

In this blog article, we approach goodwill in the more general sense, referring to any and all value of a business that is not attributable to the business’s current assets (cash, accounts receivable, etc.) or its tangible assets (inventory, furniture, equipment, etc.). Overall goodwill can be further broken down to enterprise goodwill (also known as “business goodwill”) and personal (or professional) goodwill.

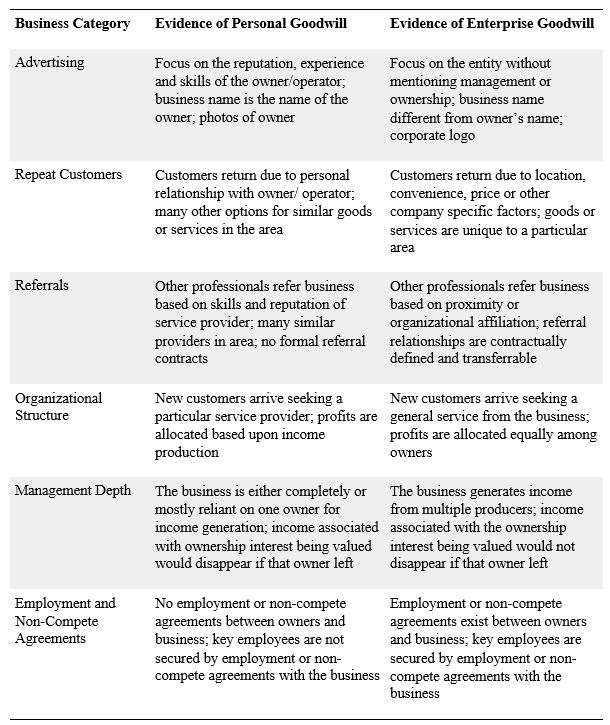

- Enterprise goodwill is derived from characteristics specific to a particular business, regardless of its owner or employees working within the business.

- Personal goodwill is value associated with a particular individual working within the organization, rather than the characteristics of the business itself.

Some of the indicators of enterprise and personal goodwill are as follows:

From a valuation standpoint, one might question why the division between personal and enterprise goodwill matters. In fact, it depends on the purpose of the valuation, in many cases goodwill (personal or enterprise) is not allocated from overall company value. The total goodwill of the business is merely incorporated as part of its total enterprise value.

For example, for a valuation prepared for gift or estate tax purpose we usually determine the company’s total value as a going concern. The resulting value often exceeds the value of the company’s tangible and monetary assets, indicating the existence of goodwill. However, the resulting goodwill is rarely further analyzed and allocated into the enterprise and personal goodwill.

Similarly, under GAAP accounting rules, goodwill on the balance sheet represents the premium for buying a business above and beyond the identifiable assets of that business. Accountants take the purchase price and subtract the fair value of company’s identifiable tangible and intangible assets. What is left, and cannot be allocated, is goodwill. For this purpose, personal goodwill is not considered a separate asset, except as it may be captured in the value of a non-compete agreement.

In other cases, like the sale of a business, the distinction between enterprise and personal goodwill could matter. One such case would be to assist in structuring a business transaction. In an acquisition, it may be beneficial to segregate out personal goodwill, since a buyer paying proceeds directly to the seller specifically for the personal goodwill (rather than as proceeds for the value of the company).

Another reason for delineating personal and enterprise goodwill pertains to the process of evaluating the total consideration to be paid by the purchaser of a business. A buyer will be willing to pay only for the portion of the intangible value of an enterprise that can be transferred upon consummation of the transaction. Based on the characteristics detailed above, this often results in only enterprise goodwill continuing with the purchaser. However, a transaction can be structured such that a portion of the personal goodwill, and its associated benefits, can transfer to the acquirer. This is often completed through the use of employment agreements.

Once the existence of personal goodwill has been identified, the next step is to calculate its value. This is generally accomplished using the “with and without” method.

The with and without method of determining personal goodwill is an income approach that attempts to value a business using two scenarios:

- with the particular individual continuing to work in the business, and

- without the individual’s continuing involvement.

The with and without method utilizes cash flow models to project the revenues, expenses and net cash flows that a business would expect to realize under each scenario. Under the “with” scenario, the projections usually reflect the overall assumptions and cash flow projections for the business “as is.” As a result, this scenario includes the value attributable to personal goodwill of the subject key individual.

The “without” scenario assumes that the enterprise would earn less revenue due to the loss of the subject individual. While the model may also assume that the subject company could hire a replacement for the key individual, most experts assume that it would take several years until the new individual could generate revenues and earnings comparable to those generated by the departing individual. Therefore, this scenario reflects a lesser value due to the entity’s loss of involvement by the individual.