Business valuation experts are called upon to value various ownership interests in businesses, ranging from the value of very small, owner-operated businesses, such as laundromats, pizzerias, or specialty contractors who operate from an outfitted pickup truck or van, to complex equity ownerships of larger companies that are ready to go public. These companies are valued for a wide array of reasons, ranging from determining the value of the business for equitable distribution in a matrimonial matter to shareholder disputes; from estate or gift tax valuations that support tax return submissions to use in a transaction of a business between a buyer and a seller.

But these reports generally apply complex valuation, financial, economic, and accounting theory that are often intelligible to only to those well versed in such matters. To that end, the following is a quick summary of business valuation theory for those dealing with business appraisals but are not versed in them.

The Value Equation Simplified

There are three ways to consider business value from an economic perspective; (1) what are the expected economic benefits worth to a potential buyer; (2) is there market evidence of what others would pay for a similar interest under similar circumstances; and (3) what would it cost to replicate the assemblage of assets necessary to generate the same economic benefit?

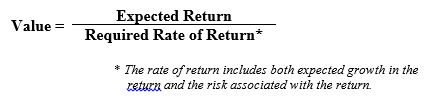

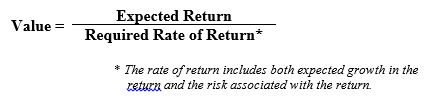

In its basic form, the valuation equation is quite simple and understandable. In such, value is computed as the expected economic return divided by the required rate of return, where that rate of return considers both growth in the expected return and the risk in the expected return.

So what is the expected return? From a business appraiser’s point of view, the expected return consists of the expected future economic benefits. Think of it this way. If you were considering buying 100 shares of Apple stock for your 401K, why would you buy it? It should be obvious that you would buy it if you thought you were going to get a return on the investment – in this case a return in term of price appreciation and/or dividend payments. Similarly, an equity investor in a private company would be looking to future profits, distributions, or cash flows available to an equity holder.

Expected Return

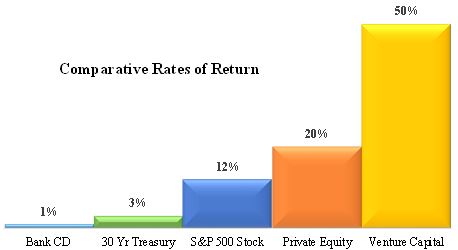

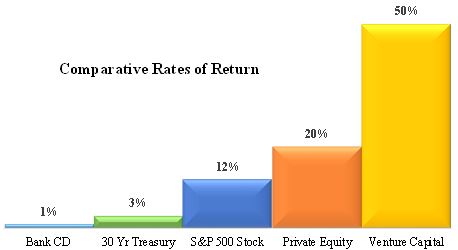

Regarding the required rate of return, it is a general truism that the greater the risk, the greater the required rate of return. An investor wants to be compensated for taking more risk. The following chart illustrates this in the market place.

Bank CDs, which generally have short return periods – say 3 months to 3 years, pay very low rates of interest – or in business appraiser speak – have low required rates of returns. Why? There isn’t much risk. The maturity is relatively short, the bank promises to pay back the full amount of the principal, and the CD is insured by the Federal Government through the FDIC. Thirty year treasury bonds are equally guaranteed by the government so have little risk. However, they have a 30 year maturity date, so there is inflation risk – the potential that rates will rise and the investor, who has locked in a return for 30 years, will miss out on higher future interest rates. Therefore, the rate of return is higher.

Similarly, publicly traded stock and privately held stock have even higher required rates of return. There is no guarantee of value – not by the government, not by the market, and not by the company. Publicly traded companies, however, are generally larger, more established companies, have strong levels of regulatory oversight by the SEC, and a board of directors who have a fiduciary responsibility to act on behalf of equity holders, not insiders. Therefore publicly traded stock is seen, in general, as less risky than privately owned company stock. Certainly the stock in publicly held companies is more liquid. Finally, venture capitalists require much higher returns for taking risks in investing in startup companies, many of which may not have a completed product or a proven business model.

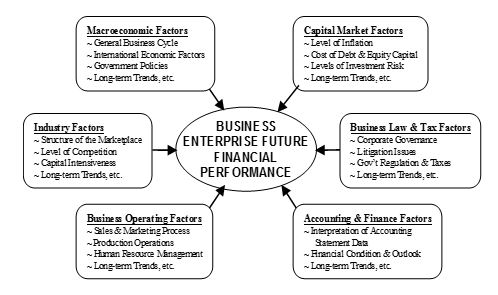

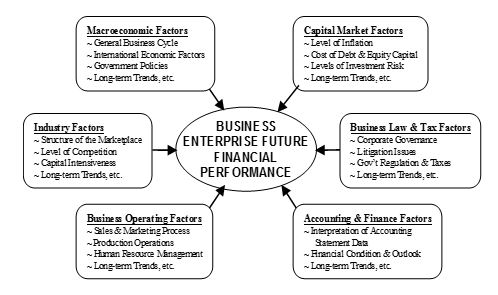

While the above returns are relatively easy to understand in terms of risk and rewards, in practice a business appraiser considers several sources of risk. For example, let’s assume a company owns and operates a chain of convenience stores with gasoline stations and makes a consistent amount of profit. Now suppose the Federal EPA requires new and improved gasoline storage tanks to reduce potential leakage and pollution that will cost hundreds of thousands of dollars to install for each location. That is now requires money to be spent on facilities that would have otherwise been available to the owners of the company. All other things equal, that loss of available funds to the owner reduces value – we have reduced the numerator in the valuation equation (above). Looking at it another way, if the business is sold and the tanks have not been replaced, the new owner will have to replace the tanks and will not pay the seller for the value derived as if the tanks had been replaced. In the same way, the following diagram illustrates many of the factors that business appraisers may consider when attempting to quantify risk.

Expected Growth

The final component in the value equation is growth. Think of growth this way: All other things equal, a company that is growing is more valuable than a company that is not – the economic benefit in the former rises over time; the economic benefit of the latter does not. It is the business appraiser’s job to estimate growth in the Expected Return. That growth may be constant, in which case the value model becomes simpler, or it may be variable, in which case a more complex valuation model may be employed to derive the value estimate.

Once the business appraiser has somewhat of a handle on these three factors, the appraiser can employ one or more of three valuation approaches, the income approach, the market approach, or the asset approach.

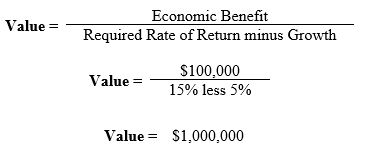

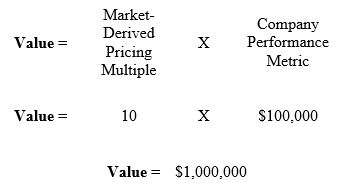

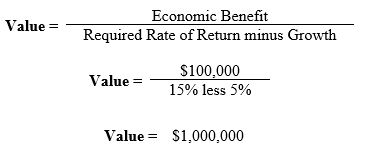

Let’s walk through an example by assuming a company generates an economic benefit to equity holders of $100,000. What is the value of the equity?

Value from the Income Approach

When employing the income approach there are several methods that can be used. The one following should look familiar. Let’s assume the $100,000 return to equity to holders and that the business appraiser has determined that the required rate of return associated with those equity return benefits is 15 percent. Let’s also assume that the appraiser as determined that the company will grow continually over time at a 5 percent rate. The value of the equity is $1 million, as follows:

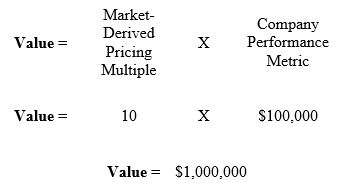

Value from the Market Approach

Employing a market approach to value, a business appraiser will seek to find companies “similar enough” to the subject company from which it can derive valuation multiples, much akin to how real estate appraisers value homes – by looking for similar sales and adjusting compare to the subject home.

So let’s suppose the business appraiser looks in the market, whether at public companies’ trading prices or private company transactions, and derives a market multiple for the metric of 10 times. Applying that multiple to the subject company’s metric of $100,000 generates a value indication of $1 million.

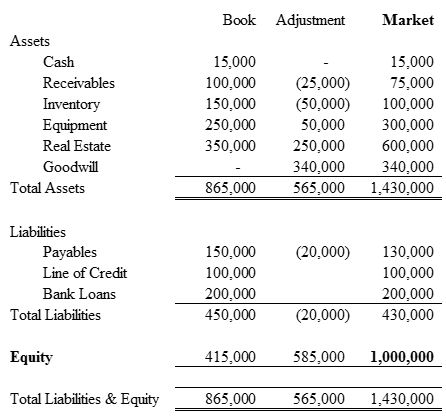

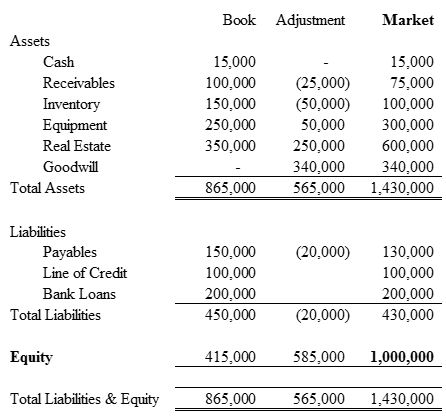

Value from the Asset Approach

The asset approach simply takes the reported accounting book value of the company’s balance sheet and converts it to market value. The theory is simple:

If Book Value of Assets – Book Value of Liabilities = Book Value of Equity

Then

Market Value of Assets – Market Value of Liabilities = Market Value of Equity

Illustratively, the following balance sheet shows the accounting book value of the company with a book, or accounting value of equity of $415,000. By adjusting the book value to market value, through analysis and appraisal of specific assets, including any not reported on an accounting basis – such as goodwill or other intangible assets, the market value of equity in the amount of $1 million is derived.

So employing the three approaches to value, income, market, and asset, all of which measure risk and returns in some way, derive a value indication of $1 million for the equity of this example company.

In addition to the above, there are a couple other concepts worth noting: level of value and standard of value.

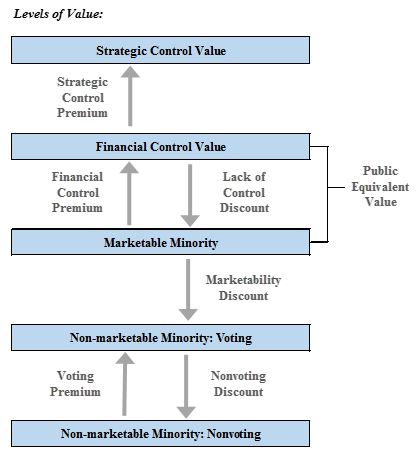

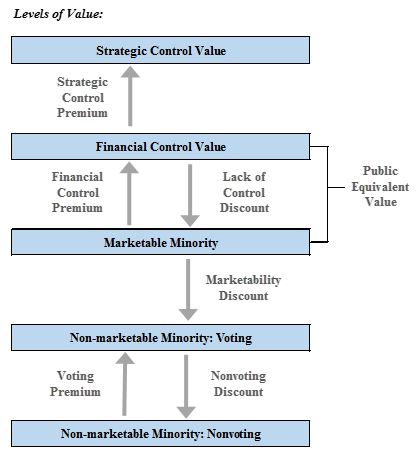

Level of Value

Level of value relates to the specific ownership interest that is the subject of the business appraisal. Different equity ownership interests in the same company may have varying levels of liquidity, or marketability, and control. Depending upon what is valued, adjustments for those differences must be accounted for, usually in terms of discounts or premiums. If a business appraiser’s value computations derive a control level value and their assignment is to value a non-control minority equity value of a privately held company, they will likely make adjustments to the pro-rata value for identifiable differences in the lack of control and lack of marketability as between a control interest and a closely held minority, non-control interest in the same company.

The following chart illustrates the relationships between the various levels of value.

Standard of Value

The standard of value assumed in the business appraiser’s analysis can impact the value conclusion. The standard of value will likely vary, depending upon the purpose and venue for the business appraisal. For example, the fair market value standard assumes a hypothetical buyer and seller on a financial transaction basis. If a business appraiser was valuing a non-control interest, the value conclusion would have to be on a non-control basis – and a discount for lack of control may be appropriate. However, in a shareholder litigation, statutory fair value is often the standard of value. Most state statutes and related case law require that the oppressed minority shareholder not be further oppressed by receiving value for their interest at a “discounted” basis that a control shareholder would not suffer.

Fair Market Value: Fair market value is defined as “the price at which property would change hands between a willing buyer and a willing seller, neither being under a compulsion to buy or sell and both having reasonable knowledge of the relevant facts.” Originally derived from tax-related valuations, IRS Revenue Ruling 59-60 is a great source document to understand fair market value. FMV is still applicable for tax compliance valuations, and is the basis for the standard of value in many other venues, such as divorce litigation.

Fair Value: Fair Value is a standard of value often used in statutory dissolution and oppression cases and its meaning and impact on value can vary from venue to venue. For example, it identified in New York State Consolidated Laws, Business Corporations, Article 11 – Judicial Dissolution as the basis for distribution and has generally been interpreted in the courts as a shareholder’s “proportionate interest in ‘going concern value’ of a corporation as a whole, that is, what a willing purchaser, in arm’s length transaction, would offer for corporation as operating business.” (638 New York Supplement, 2d Series / 87 NY.2d 181). There is also a different kind of “fair value” standard for financial reporting, which is defined in detail in FASB (Financial Accounting Standards Board) pronouncements.

Synergistic Value: Synergistic Value is the unique value to a particular buyer who expects returns outside, or in addition to, the returns of the business enterprise itself because of the expected synergies such as: the consolidation of back-office operations, economies of scale, elimination of competition, product or market synergies, and/or increased purchasing power.