Which of these businesses do you think is riskier: A pizzeria on a busy street in some village’s downtown business district, or a company with five pizzerias at similar locations in five villages?

Chances are, the single-location business faces more risk. Think of the effect a broken water main would have on the day’s receipts, or the impact a new competitor might have on foot traffic. Larger businesses tend to have more diversified products, suppliers and customers, all of which mitigate risk.

Why is risk important in business valuation? Because there is an inverse relationship between risk and value. The greater the risk, the lower the value. That’s why business valuation professionals often apply a size premium, also known as a small-company risk premium, to capture the risks and the corresponding additional returns investors expect to earn from the stock of small companies versus larger ones.

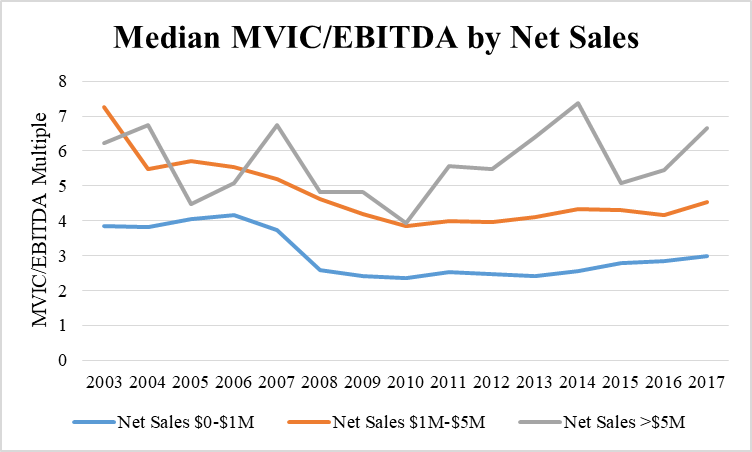

How does this principle apply to small-business valuations? In order to shed some light on this question, we analyzed data for small, private-company transactions from 2003 to 2017 provided by Pratt’s Stats Private Deal Update for the second quarter of 2018 (also known as Deal Stats Value Index). Valuation professionals commonly employ these transactions to derive benchmark ratios, or multiples, for use in the market approach to valuation.

One such earnings multiple is MVIC/EBITDA. This is the ratio of the market value of invested capital (think “sale price”) to earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization, where invested capital equals equity plus debt. A business with $250,000 of EBITDA that sells for $1 million has an MVIC/EBITDA multiple of 4.

Private Deal Update provides median MVIC/EBITDA data by year from 2003 to 2017 for companies in three net sales ranges: up to $1 million, $1 million to $5 million, and greater than $5 million.

The chart clearly shows that companies with the lowest net sales garnered significantly lower EBITDA multiples than did companies in the middle and upper sales ranges. Companies in the highest revenue range tended to sell at the highest multiples, with the distinction more pronounced since the end of the Great Recession. In 2017, the most recent year available, the largest companies sold at a median of 6.7 times EBITDA, compared to 4.5 times EBITDA for the middle range and 3 times EBITDA for the smallest companies.

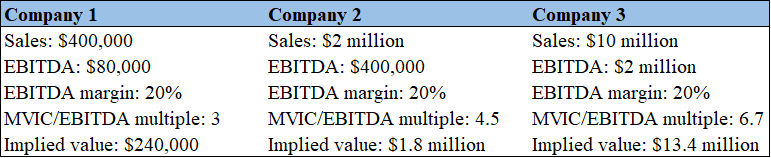

Consider a scenario in which those MVIC/EBITDA multiples are applied to three fictitious companies, each of which has a 20 percent EBITDA margin:

All three companies exhibit the same degree of profitability as measured by EBITDA margin, but the small company’s implied value is just 60 percent of annual sales, while the large company’s implied value is 134 percent of annual sales.

The data provides a strong endorsement for the application of a size premium in transactions involving small businesses. As is often the case with sweeping pronouncements, however, there are caveats to bear in mind. We’ll leave you with a few:

- The smallest companies in the dataset – those with up to $1 million in annual sales – tended to be more profitable than larger companies. This might mitigate, to some degree, the effect of their lower multiples.

- There are many other factors beyond size – and beyond the scope of this article – that can affect a company’s valuation multiples.

- And finally, the Private Deal Update data includes a melting pot of transactions in a variety of industries, from manufacturing to retail to IT. Each of these industries is made up of numerous subdivisions, each with unique characteristics, financial and otherwise.

Here at Advent, we won’t casually apply a broad analysis, but will drill down into the data to consider these unique characteristics and their impact on risk, and therefore value.

For more information, contact Advent Valuation Advisors at 845-567-0900 or info@adventvalue.com.