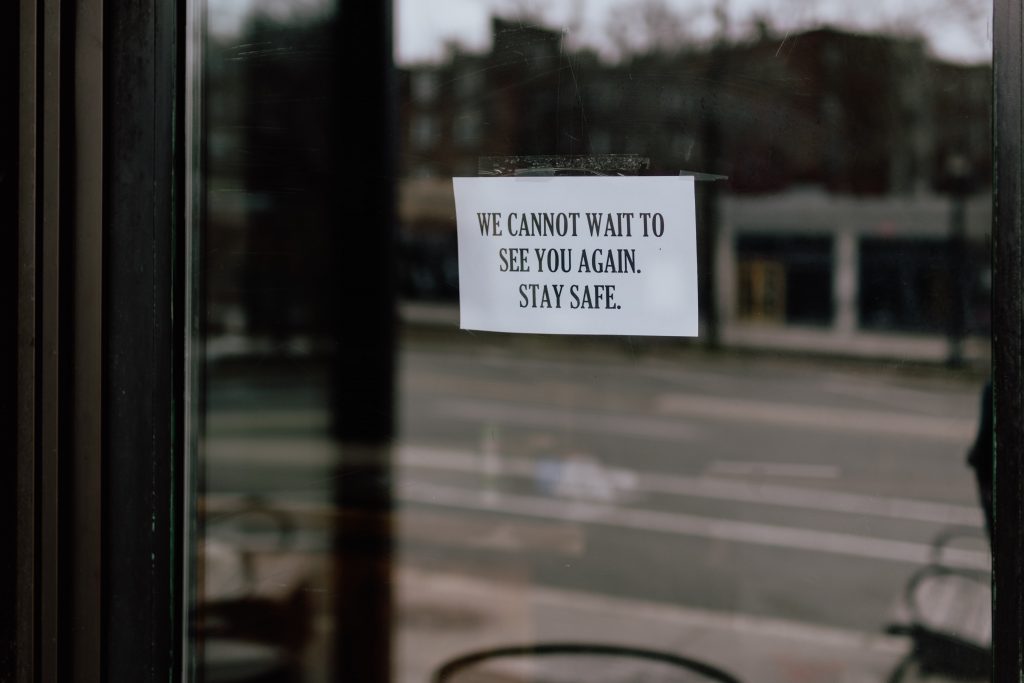

There is a substantial amount of information out there about how small businesses should respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, and the fear and uncertainty about the virus and what comes next. It is not hard to find articles about how to protect employees, customers and suppliers from infection and how to talk about the virus. In this article, I will focus on what businesses and their lenders and stakeholders must do to minimize losses and maximize financial stability in this unprecedented time.

Businesses, even high performers, need to consider the detrimental impact on cash flow resulting from the steps taken to slow the spread of the virus and “flatten the curve” of new cases. Some businesses are completely closed, while others are suffering disruptions such as reduced hours due to government restrictions. Supply interruptions are hurting business as well. Regardless of the industry, the inability to generate adequate cash flow endangers the ability to meet obligations to lenders, trade creditors and investors. Here are some things owners can do to navigate the crisis.

Generate Projections

While no one really wants to look, it is critically important that businesses recast operating cash flow projections or generate new ones. This includes revising assumptions, forecasts and business plans to reflect the new reality. Prepare projections that consider the best and worst cases for the next few months and longer.

If management hides its head in the sand, the company is likely not going to survive. Hiring an experienced restructuring advisor and legal counsel early can provide credibility when dealing with lenders, creditors and investors. It may also preserve business value.

Develop a New Financial and Operating Plan

Triage is important. Some businesses are proficient at managing operations in times of stress. However, few companies have ever faced a dramatic, escalating crisis like the current one. Businesses have little choice but to pivot meaningfully, and planning is key to survival. This planning must address the new reality reflected by revised and updated cash projections and should include these steps:

- Protect working capital. This includes taking an inventory of existing working capital, drawing on existing lines of credit and developing and implementing a cost-reduction plan to achieve positive cash flow. Cash is king and needs to be preserved.

- Identify any collateral that could secure additional financing. Seeking such financing may not be feasible in the current environment, but this may change. To the extent a company has unencumbered assets, additional liquidity may be easier to arrange. It is important to identify assets that might be available to secure financing, including real property, inventory and accounts receivable.

- Monitor federal and state government relief initiatives.

- Consider working with a professional financial advisor and legal counsel to open lender communications. Some business owners who need to obtain financing on an emergency basis think that engaging a professional is a sign of weakness or requires cash that the company would prefer not to use. In fact, involving professionals in the process provides significant credibility when asking creditors for relief. Lenders and stakeholders may be more willing to respond quickly and positively if provided with information that has been reviewed by the company’s financial advisors. Attempting to save money by not hiring a professional can put at risk the ultimate success of discussions with lenders and creditors.

What if maintaining existing financing is not viable?

Once management is aware of the business’s inability to perform, it must work with stakeholders to establish strategies for employees, lenders, suppliers, customers and investors. This strategy must include developing communication plans for each of these groups. Retaining advisors is critical to address potential debt defaults, contractual performance defaults and other obligations.

Management must have a plan in place to address these issues, and outside help may be necessary to weigh the options, minimize risk and maximize value. Management is accustomed to operating in a normal environment and may have no experience dealing these kinds of challenges. If the company has a board of directors, outside guidance is critical to its duty-of-care responsibility.

It is important to determine what requests for relief from lenders are necessary to allow the business to continue to operate in this unpredictable environment. Considerations include what is needed to avoid default on short- and long-term financing obligations and what is needed to maintain relationships with vendors and suppliers. This includes “asks” that reflect reduced operations. Relationships with lenders, investors and other creditors can be more easily maintained if communication is open and frank and if professional advisors help the company determine which “asks” are likely to be successful.

This article merely scratches the surface of the complexities businesses face because of COVID-19. This disaster will likely rewrite the playbook for financial and operating restructuring. It is clear that credit providers and businesses, in order to survive, must be unified in focusing on preserving business value until the “new normal” emerges.

If you have questions about how to address your business’s financial difficulties, please contact the professionals at Advent Valuation Advisors.

Price is specific to an individual buyer and seller. It’s the amount of cash (or its equivalent) for which anything is bought, sold or offered for sale. It requires an offer to sell, an acceptance of that offer and an exchange of money (or other property). Some strategic or financial buyers may be willing to pay more than others because they can benefit from economies of scale or synergies that aren’t available to all potential buyers.

Price is specific to an individual buyer and seller. It’s the amount of cash (or its equivalent) for which anything is bought, sold or offered for sale. It requires an offer to sell, an acceptance of that offer and an exchange of money (or other property). Some strategic or financial buyers may be willing to pay more than others because they can benefit from economies of scale or synergies that aren’t available to all potential buyers.

You wouldn’t perform a surgery on yourself. The same holds true when buying a business. Unless you’re well-versed in performing a comprehensive financial analysis of a business, it doesn’t make sense to buy one without using a due diligence and valuation specialist. A due diligence report:

You wouldn’t perform a surgery on yourself. The same holds true when buying a business. Unless you’re well-versed in performing a comprehensive financial analysis of a business, it doesn’t make sense to buy one without using a due diligence and valuation specialist. A due diligence report: